By Mustafa J. Salem, Nick Drake and Ahmed S. El-Hawat.

Tripoli, 9 May 2013:

Holocene inetr-dunal lake deposits in Idhan Obari. Edges of these lakes are rich in archaeological remains indicating that pre-historic man occupied these areas at the time.

Fezzan Region is rich in its water resources. A lot of fossil water has been left under ground since the lakes that dominated the region thousands of years ago dried up.

Most people when talking about the Fezzan think of a dry, barren and mostly unpopulated hyper-arid desert, with a few oases found within the wadis that run through this vast area. In fact the region, about 450,000 square kilomtres in size, provides much evidence of a long and interesting history of human settlement and natural development. Its diversified landscape of wadis, plains, mountain ranges and sand seas contains sediments deposited by rivers and lakes during a more humid environment as well as the remains of periodic human occupation, represented by rock art and archaeological remains.

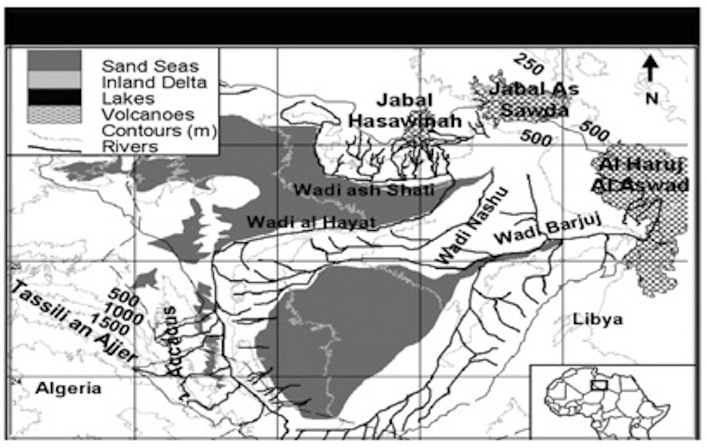

The Fezzan is a large topographic basin covering much of south-western Libya that in past humid periods has contained a vast lake reaching a maximum size of 120,000 square kilometres. The basin is bounded by the Al-Hamadah Al-Hamra plateau to the north, the Jabal Al-Sawda and Al-Haruj Al-Aswad shield volcanoes to the east, the Hamadat Mangueni to the south and the Akakus Mountains to the west.

Interpretation of the topography and geology of the Fezzan Basin suggests that its development was largely controlled by the interplay of volcanic and fluvial activity.

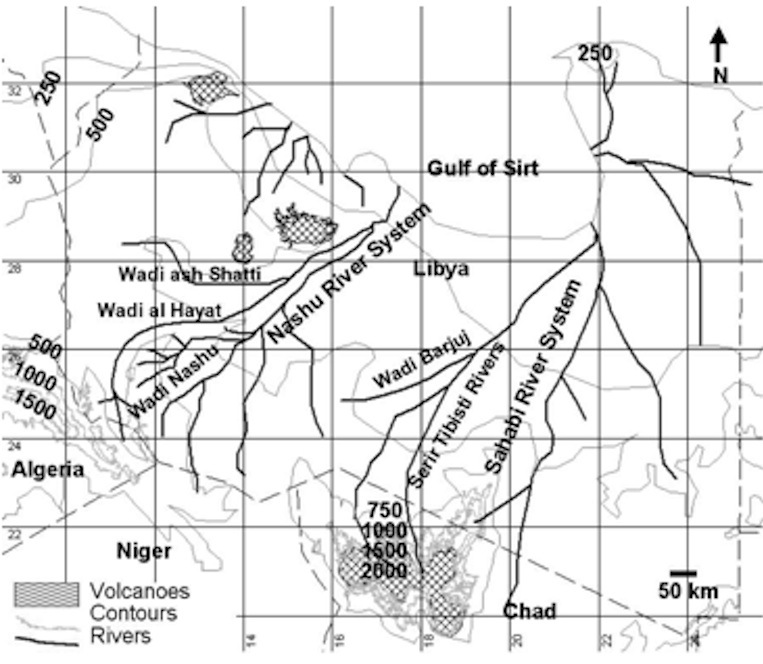

Its origin appears to lie in the late Miocene period when the region that now forms the basin contained a small river in the south called Wadi Barjuj and a large river system further north named the River Nashu and composed of channels, with tributaries that include Wadi al Ajal (Al Hayat), and Wadi ash Shatti (See Fig.1).

Both these rivers ran from west to east-northeast emptying their loads in the Mediterranean Sea at Gulf of Sirte. Another major river system called the Sahabi River ran through the central and eastern Libya fed by branches issuing from the Tibesti mountains and Kufra region to the south and also terminating in the Gulf of Sirte (Fig. 1).

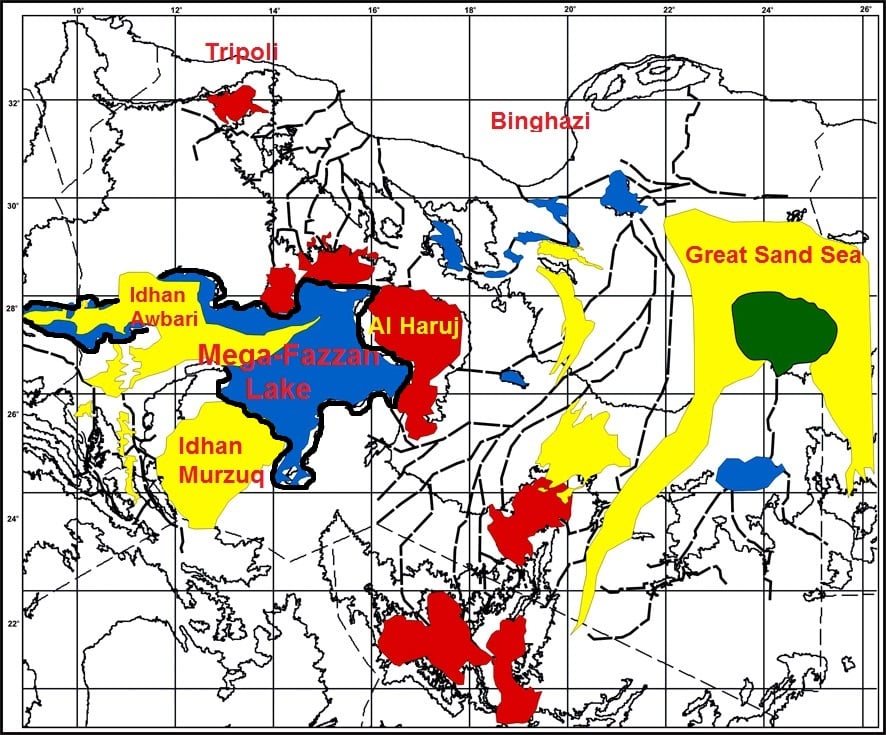

These rivers started to be affected by volcanic activity on the east of the basin with the development of Jabal Al-Sawda from 12.3 to 8.0 million years ago (MA) and Al-Haruj volcanic shield from 6.0 to 4.0 MA. As these volcanoes grew they first cut off Wadi Nashu and then eventually Wadi Barjuj. The result of these two events was a large closed basin in the Fezzan (Fig.2) (~350,000 square kilometres) that could sustain a very large lake during humid periods (Fig 3).

Large areas of exposed sedimentary rocks in the area of the proposed lake are the evidence for its existence. The sediments consist of lacustrine limestone deposited in humid periods inter-bedded with Aeolian sands deposited in arid periods(Fig.4) .

The earliest deposits examined are Pliocene in age. Humid periods appear to correspond to interglacials and aridity is found in glacials.

It is possible that, from about 120,000 years ago (ka), water availability was more restricted during interglacial humid periods than previously, leading to the development of many small lakes in the Fezzan Basin, rather than the single giant lake that had existed between about 200 and 420 ka. Sediments indicating these small lakes are currently exposed in the inter-dune areas, between the sand dunes of Idhan Murzuk and Idhan Obari (Figs 5 and 6). These small inter-dune lakes in Idhan Obari and Idhan Murzuk attracted the prehistoric hunters and animal herders and on their edges are found archaeological and faunal remains (Figs 7 ,8 and 9). As these lakes finally dried up between five and three thousand years ago, human occupation concentrated around the few remaining springs and in these regions, villages and small towns developed, one called Germa (Jarmah) eventually formed the capital of the Garamantean civilization that flourished in the region between 2,400 and 1,800 years ago by introducing a diverse oasis agriculture and establishing and controlling trans-Saharan trade.

Prospects for the Fezzan Region in future

The Fezzan Region not only has a diversified landscape, but is also rich in natural resources such as fossil fuels, renewable solar and wind energy for the future, metallic and non-metallic minerals and above all, abundant groundwater resources provided by its more humid past. Though the aquifers contain fossil water, the low population in the Fezzan means that there should be enough water resources for the region for some time to come if the resource is well managed (Figs 10 and 11).

The diverse landscape of this region and its rich history makes it one of the primary sites in Libya in terms of tourism potential. This can be achieved only if the Ministry of Tourism collaborates with other concerned government organisations and if it adopts a policy that aims at developing the Fezzan as an area for cultural as well as adventure tourism. However, the fragile environment means that this needs to be done in conjunction with the development and implementation of policies on environmental sustainability and conservation of the heritage.

Promotion of eco-tourism should be adopted as a priority alongside conservation of fragile areas such as Akakus Mountains, Messak Settafet, Idhan Murzuk, Wadi Aramat, the Meghidet region and the lakes of Idhan Obari. Ideally these regions need to be protected by law, and restricted for guided tours only. Large convoys of vehicles, such as those used for off-road rallies should be restricted or prohibited. When planning conservation and preservation programmes for the region the relevant authorities (the Ministry of Tourism, Ministry of Culture, General Authority of Environment and the Department of Antiquities) could benefit from the experience of other countries with similar situations. A good example in Africa is Namibia with its national conservation programs and those of the Namib Desert in particular.